What’s a logic grid?

Logic grids are one of those things that best explained by starting with an example.

An example logic grid puzzle

A logic grid typically presents a list of clues, such as:

- Amy’s birthday is in April.

- Bintang is 7 years old.

- Chandra was born in September.

- Amy is 8 years old.

These clues would be accompanied by a grid:

The player would then put ticks and crosses on the grid, solving for the birthdays and ages for all three characters. Of course, this is only possible if we assume all three characters have distinct birth months and ages; this assumption is usually implied in logic grids.

Note that the above grid is functional; press the boxes to turn empty cells into crosses, crosses into ticks, and ticks back into empty cells. You can drag click too. Feel free to try it out! Open the following callout to reveal the solution:

Example logic grid solution

Amy is 8 and born in April.

Bintang is 7 and born in January.

Chandra is 9 and born in September

Formal description

Formally, logic grids admit quite a concise description: Given categories, each with distinct elements, the player is given clues about the categories and elements, leading to a unique bijection between every pair of categories.

For example, the previous puzzle has 3 categories, each with 3 elements, and 4 clues. The solution was a unique bijection between names and birthdays, birthdays and ages, and names and ages.

Interestingly, logic grids are solvable in polynomial time, given “simple” clues, and other constraints! In fact, some solvers like this paper can give provably correct, human-like reasoning for the solution, still in polynomial time!

What about brute force?

Note that if you have categories each with elements, there are

possible bijections to brute force, since

- Fixing a category’s elements, the first element has choices to map into another category, the second , and so on, so bijections between any two categories of equal size .

- Repeat step 1 times, pairing up with a new category each time. Any remaining bijection(s) are uniquely determined by composing the existing bijections.

In other words, polynomial time is quite efficient!

Useless logic grids?

So we have

- Polynomial-time solvers

- Explainable solvers

- Probably correct answers

These are all very nice properties for a problem class to have. (I won’t go into why these properties hold here. I refer interested readers to this paper.)

At the same time, you can say that logic grids are kind of “useless.” You need:

- All categories known and unique.

- All elements known and unique.

- All clues correct.

- Non contradicting clues.

- Clues result in a (unique) solution.

If you knew all 5 above statements were true, you know so much about the problem you kind of already have the answer!

Useful Logic Grids

Logic grids may have a lot of constraints, but they’re useful for solving puzzles that satisfies those constraints. Even when the puzzle does not look like it can be solved with a logic grid. For example, consider the following problem:

Key deductions

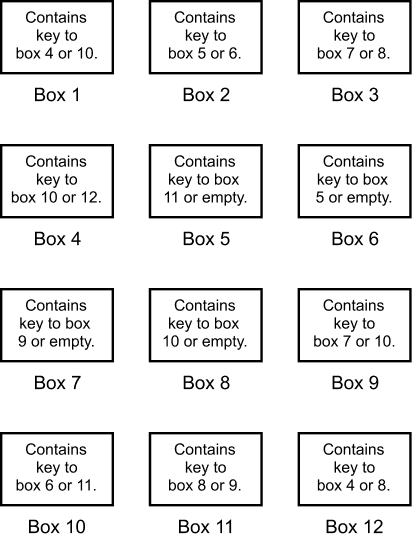

You are given 12 locked boxes. They all require different keys to be opened, and there are no duplicate keys.

You are given keys to boxes 1, 2, and 3, which are not in any other box. Besides boxes 1, 2, and 3, 6 of the other boxes contain a single key, while two of the remaining contain nothing and the third a prize.

Which box, 1, 2, or 3, when opened leads to a sequence of keys and openings that gives you the prize? The longest sequence of boxes, starting from box 1, 2, or 3, ends with the box with the prize. All keys are retrievable.

This puzzle was taken from Return to Montague Island, puzzle 1.1 by R. W. Schmittberger.

Personally, a lot of the difficulty of this puzzle comes from figuring out how to effectively structure the given information. It’s tempting to create a graph with 12 vertices, whose directed edges represent the potential keys. Perhaps, some sort of graph traversal can get us the answer.

Unfortunately, this graph strategy doesn’t work so easily. In particular, since all keys are retrievable and unique, you need to visit all boxes (vertices) in the graph. At the same time, you have three starting positions to consider and at every point you have up to two choices of where to go next.

Perhaps there is a more clever graph representation and algorithm for this problem. But as we’ll soon see, logic grids make problem feel trivial. Please open the callout below to see the logic grid solution:

Key deductions solution

Construct the following grid:

Put crosses on every cell that violates the clues on the boxes. Doing so, you may discover:

- Box 4 must contain the key to box 12, since it is found nowhere else.

- Box 12 cannot contain the key to box 4, else both boxes would not be retrievable. Thus box 12 contains the key to box 8.

- Then box 3 contains the key to box 7.

- Then box 11 contains the key to box 9.

- Then box 9 contains the key to box 10.

- If box 10 contained the key to box 11, then box 9,10,11 would form a loop, so box 10 must contain the key to box 6.

- Also, box 2 contains the key to box 5.

- Furthermore, box 1 has the key to box 4.

- Then box 5 has the key to box 11.

- Boxes 6,7,8 are empty.

- Starting with box 2 leads to boxes 5, 11, 9, 10, and 6, which is the longest sequence. Thus the prize is in box 6.

It’s a lot of steps, but many of them (especially step 1) become trivially obvious with the logic grid. Furthermore, you can actually save space by constructing the following grid:

Namely, fill each cell with the two possible outcomes of each box, and cross out the ones you deduce are incorrect.

Useless logic grids

Who's the liar?

Fatima and Amara come from a land where some always tell the truth, and the rest always lie.

Amara says, “Either Fatima lies, or I am truthful.”

Are Fatima and/or Amara liars?

Usually, we solve puzzles like this using a truth table. Can we use a logic grid? What should the grid be? Something like this?

Or maybe something like this?

Solution spoiler alert! Fatima is truthful and Amara is truthful . So can’t we just do:

Recall that in the key deductions puzzle, we used the fact that a tick mark causes crosses to appear in all cells that share a row or column with the tick in the same category. If we allowed multiple tick marks in each row or column, we would lose out on this trick. Do logic grids even work when we allow multiple ticks like this?

Non-bijective logic grids

Recall that logic grids need:

- All categories known and unique.

- All elements known and unique.

- All clues correct.

- Non contradicting clues.

- Clues result in a (unique) solution.

We try to relax 1 and 2 to:

- All categories known.

- All elements known.

Interestingly, the logic grid remains an incredibly effective way to encode information! (More formally, the polynomial time properties from earlier still hold with some minor caveats, though the proof of this is far beyond the capacity of this blog post. It essentially boils down to a polynomial time reduction.)

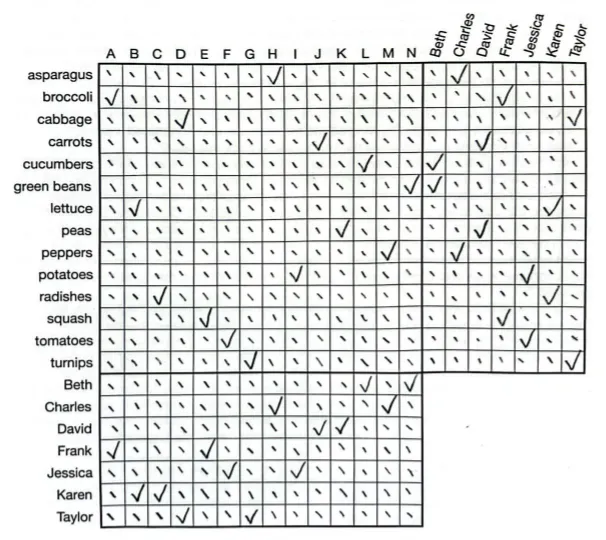

For example, here’s the grid for Montague Island Mysteries, puzzle 4.4 that I solved the other day:

Lying logic grids

We now only need:

- All categories known.

- All elements known.

- All clues correct.

- Non contradicting clues.

- Clues result in a (unique) solution.

We try to relax 3, 4, 5:

- Clues may be incorrect, but it is known how many are incorrect.

- Clues may contradict.

- Clues may result in no solution, but there exists a subset of clues that result in a solution, satisfying at least the number of known correct clues.

Let’s explore what these mean through a puzzle.

Murder mystery

A murder has occurred! Alistair the butler is innocent, but one of the staff and one of the guests are guilty! The guilty party’s statements cannot be trusted. All other statements are true!

Staff statements

- Alistair: Either Jessica is innocent, Evelyn and Sandy are both innocent, or all three are innocent.

- Evelyn: If Beth is guilty, then so is either Grant or Lyle. If Jessica is guilty, then Grant and Lyle are innocent.

- Grant: If Molly or Sandy is guilty, then Beth, Charles, and Karen are innocent. If Lyle is guilty, then David, Frank, and Jessica are innocent.

- Lyle: If Evelyn is guilty, her accomplice is David, Frank, or Jessica.

- Molly: If Frank is guilty, his accomplice is either David or Evelyn. If Karen is guilty, her accomplice is Grant or Lyle; but if David is guilty, Grant and Lyle are innocent.

- Sandy: If Charles is guilty, then so is either Grant or Lyle. If Grant is guilty, then David, Frank, and Jessica are innocent.

Guest statements

- Beth: If Evelyn is guilty, then David and Frank are innocent. If Molly is guilty, then David and Jessica are innocent.

- Charles: If Sandy is guilty, then David and Frank are innocent.

- David: If Beth is guilty, her accomplice is not Grant or Lyle. If David is guilty, his accomplice is not Evelyn or Sandy.

- Frank: If Grant or Lyle is guilty, then Beth and Karen are innocent. If Molly is guilty, then her accomplice is Beth, Charles, or Karen.

- Jessica: If Grant or Lyle is guilty, then Charles and Karen are innocent.

- Karen: If Charles is guilty, his accomplice is either Evelyn, Molly, or Sandy. If Frank is guilty, Evelyn and Sandy are innocent.

This puzzle is from Montague Island Mysteries, puzzle 12.4.

At first glance, this puzzle looks daunting. There are 12 different parties. Each of them gives up to two statements, and these statements involve “and”, “or”, and “if.” It feels like there’s no solid ground to start on.

At this point, you’ve probably guessed that logic grids can be used to solve this problem. This is a post about logic grids, after all. Indeed, a very clever logic grid can be used to solve this problem. Here’s a pretty big hint: If a statement is corroborated by two or more guests (or staff, respectively), it must be true.

Please expand the callout below for the full solution.

Murder mystery solution

Construct the following grid:

Note that we exclude Alistair because we already know he’s innocent. Place an S in each cell whenever a staff member has made a statement ruling out that staff-guest pair. Place a G if a guest has done so.

Whenever a cell contains more than 2 “S” or 2 “G”, counting them separately, then that pairing is impossible. Otherwise, there would be more than one liar in the staff or guest category.

Doing this repeatedly will reveal other certainly innocent staff and guests. In the end, every pairing bu one can be eliminated by this method. The exception is Molly and Frank whose statements eliminate their own pairing but is never corroborated. They are the guilty pair.

We can generalize this technique; If there are liars in a category, find all claims corroborated by claims in the category. Repeat this, taking account of any new information deduced.

I hope you found the above puzzle as interesting and fun as I do. I honestly think it’s a really elegant trick, but one question did linger for me: What if the number of liars is unknown?

Bounded lying logic grids

We now only need:

- All categories known.

- All elements known.

- Clues may be incorrect, but it is known how many are incorrect.

- Clues may contradict.

- Clues may result in no solution, but there exists a subset of clues that result in a solution, satisfying at least the number of known correct clues.

Let’s try to relax 3 further:

- Clues may be incorrect, but there is a non-maximal bound on how many are incorrect.

Once again, lets explore what the new condition 3 means through an example.

Pilfer puzzle

A robbery has occurred in the same mansion! Fewer than 4 guests were the thieves. Their statements may be true or false. All other statements are true! Police investigation has also shown that neither Danny nor Brianna makes a true statement unless he or she is innocent.

- Aria: Either Brianna or Cheryl is guilty, but not both.

- Brianna: Cheryl is innocent, and there were three thieves.

- Cheryl: Steven is innocent, and there were three thieves.

- Danny: Either Kelly or Steven is guilty, but not both.

- Kelly: I am innocent, and there were two thieves.

- Steven: I am innocent, and there were three thieves.

- Taylor: Either Aria or Danny is lying, but not both.

This puzzle is from Beyond Montague Island, puzzle 9.1.

Here are some hints:

- There is a fast way to find out the # of thieves.

- Start with Danny and Brianna’s clues first. Why would you want to do this?

- At least one of the thieves is not lying; this thief must be identified through elimination.

Please expand the callout below for the full solution.

Pilfer puzzle solution

Consider the bolded parts below:

- Aria: Either Brianna or Cheryl is guilty, but not both.

- Brianna: Cheryl is innocent, and there were three thieves.

- Cheryl: Steven is innocent, and there were three thieves.

- Danny: Either Kelly or Steven is guilty, but not both.

- Kelly: I am innocent, and there were two thieves.

- Steven: I am innocent, and there were three thieves.

- Taylor: Either Aria or Danny is lying, but not both.

By proof of contradiction, there are three thieves, else there are more false statements than thieves. Repeating the same technique from the previous problem, we find that Aria, Kelly, and Taylor are the thieves.

Notice what we just did: We first tried to map the problem into a type of logic grid we knew how to solve, i.e. known number of liars logic grids. At that point, we can just reuse previous techniques to solve the problem.

Conclusions

We started from a constrained problem, then generalized:

Bijective LGs → Non-bijective LGs → Lying LGs → Bounded lying LGs

Every time, our first instinct was to try and map the problem back into a logic grid class we’ve already seen. In doing so, we found a relatively powerful puzzle-solving algorithm, or more loosely, a data structure for organizing puzzle-esque information.

The Montague series

Many of the puzzles from this talk come from the following books:

If you enjoyed them, (I certainly do!), I highly recommend getting a copy. They’re surprisingly cheap and very well made. I am not sponsored. Sadly, the author has passed and is no longer with us.

I hope this post has been an enjoyable read. If you have any questions, concerns, or additions, please feel free to reach out!